When Cameras Took Pictures of Ghosts

When photography was new, people used it to suggest the endurance of the departed.

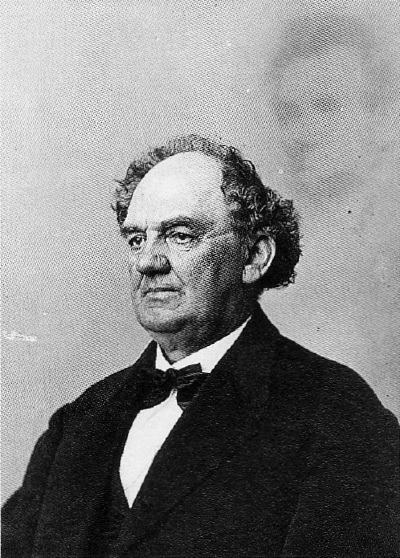

Megan Garber William Mumler‘s downfall came about, in part, because of P.T. Barnum. The world’s first known “spirit photographer” had captured an image of Barnum posed next to a ghost of an exceptionally notable variety: that of the recently assassinated Abraham Lincoln. During Mumler’s 1869 hearing for fraud, Barnum—the trickster, indignant about trickery—was called to the witness stand to testify against Mumler. Barnum would serve as an expert, the Oxford University Press notes, on “humbuggery.”

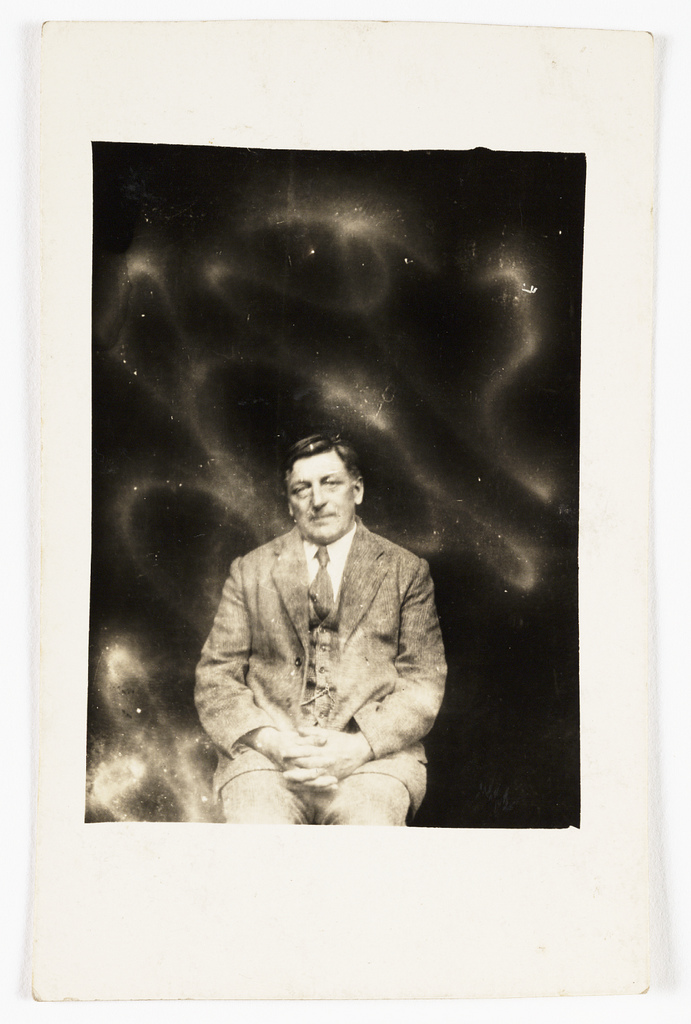

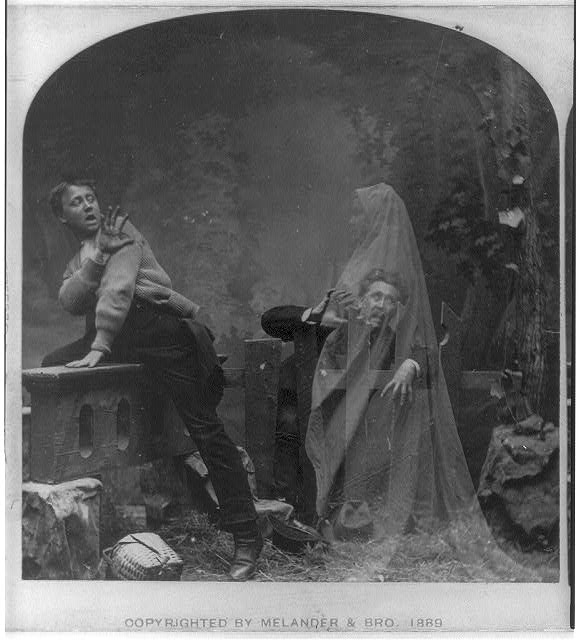

Mumler was not alone in his attempts to manipulate photography for purposes of prank and profit. Photo manipulation is nearly as old as photography itself, and what Mumler lacked in Photoshop, he made up for in ingenuity. During his hearing, fellow photographers identified nine different methods that could aid in the photographic imitation of “spirits”—including techniques like multiple exposure and combination printing. As David Brewster, in his 1856 book on the stereoscope, explained:

For the purpose of amusement, the photographer might carry us even into the regions of the supernatural. His art, as I have elsewhere shewn, enables him to give a spiritual appearance to one or more of his figures, and to exhibit them as ‘thin air’ amid the solid realities of the stereoscopic picture.

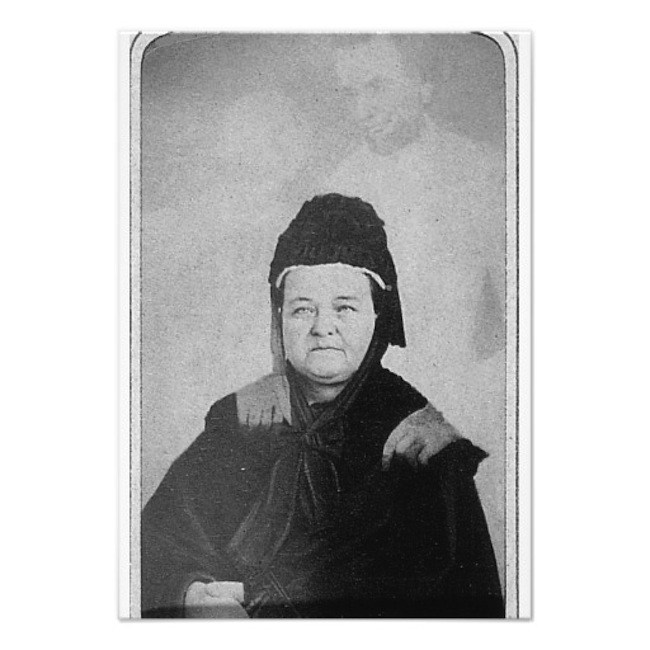

For Mumler—the first of many advantage-taking “spirit photographers”—photo manipulation was also good business. While he was ultimately selling nostalgia and comfort, what was he technically selling were portraits of clients posed alongside the “spirits” of their deceased loved ones. He sold those for between $5 and $10 apiece—which was, the OUP’s Kate Scott puts it, “a huge fee at the time.” Soon, as one history sums it up, “He grew wealthy producing spirit photos for grief-stricken clients who had lost relatives in the Civil War.”

So how did he do that work? Sometimes, he’d have images to use for his “ghosts.” During the Civil War, as families endured separations both lengthy and permanent, keepsake photographs became popular, with thousands of portraits produced. One of the most popular forms for these were cartes-de-visite, photographs mounted onto small, thick pieces of paper—trading cards, essentially. Mumler used the photos on those cards, along with similar photographs, to create his “ghosts.” He used the visages of famous figures, as in the case of Barnum’s Lincoln portrait, to create the illusion of communion with the notable. And he used images of the non-famous to create the illusion of disembodied intimacy.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Which was ingenious and cruel at the same time. Visual memories, even those of loved ones, fade. Images blur. Lines soften. Mumler took advantage of this. As Scott puts it: “If a customer shared enough information with the photographer, and if the selected face was faint and blurry enough, the resulting ‘spirit’ could convince a person who wanted to be convinced.”

Views: 245